6.4 Rembrandt as a Model in the 18th and 19th Century

The work of Rembrandt was in particular known through prints.1 However, Rembrandt was a collective name in the 18th century, from which the above-mentioned fine painting portraitists drew their inspiration, as well as the ‘ingenious’ sketching of Johann Georg Trautmann or Januarius Zick. What was not looked for, was the quiet, balanced, expressive work of the late Rembrandt: ‘His [Rembrandt’s] classic style remained in those days a closed book with seven seals’ [in translation].2 The Rembrandt Renaissance began in the second half of the 18th century and was anchored in the anti-Rococo movement, and thereby characterized and limited. His chiaroscuro was the key point. Januarius Zick heightened it for the sake of its moving effect. Johann Georg Trautmann saw everything in the mild glow of Rembrandt, quite similar to a painting of Van Ostade. Christian Wilhelm Ernst Dietrich strived after the light-shadow contrasts of the early carefully drawn portraits. Oriental attire and men with turbans which provide the pretence of mystery and heighten the atmosphere, are inextricably linked to the conception of Rembrandt. Other artists of the time saw him more soberly as a realist of the chiaroscuro, and they didn’t hesitate to compose companion pieces to real (?) works of Rembrandt, that were supposed to be more beautiful than those works of the 17th century.

Interpreting Rembrandt’s atmospheric light as mere candle-light effects was only done by simple minds, who otherwise gladly hooked up to the cozy civic interiors of the fine painters. The other extreme we see in the works of the Southern German and Austrian Baroque, for instance from Franz Anton Maulbertsch and Kremserschmidt. They show a more free and independent interchange with the Rembrandt legacy, while sometimes, with a brilliant verve in the manner of the Venetians, something new and personal is created.

Wherever a realistic painting in the truest sense was made, we see the examples of Rembrandt resurface. And where is this more appropriate than in the artist’s self-portrait, where the paying customer who desires a pompous representation is absent? The artist’s portrait with the shading hat -- when we take an external appearance as a characteristic -- can be traced throughout the 18th century with Dietrich Ernst Andreae (born c. 1680), Anton Graff (born 1736), Josef Grassi (born 1757) and Heinrich Friedrich Füger (born 1751), artists who otherwise had kept away from making naïve Rembrandt imitations.3

It is German painting of the 19th century that finally broke with the Rembrandt cult. The fact that some little-known painter would copy the Night Watch and study other paintings during a trip through Holland, cannot refute this. Hans von Marées (1837-1887), whose broody, searching character brought him into contact with Rembrandt, is an exception [1-2].4 He admired his impasto and had, as one of the few, understanding for his classic, stilled style, with which none of his predecessors could get their heads around.

When Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885) -- if you excuse this combination -- once painted in the style of the old master, he saw Rembrandt as the master of the fantastic light and of the nervous movement, which had been conveyed to him by Januarius Zick [3-5].5

1

Hans von Marées

Self portrait of Hans von Marées ( 1838-1887), ca. 1860-1862

Munich, Neue Pinakothek, inv./cat.nr. 14548

2

Hans von Marées after Rembrandt

The Entombment, c. 1862

Private collection

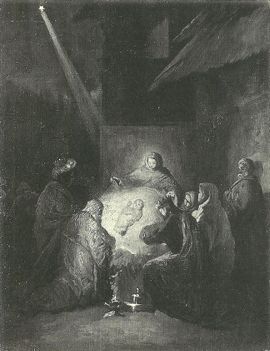

3

Carl Spitzweg

The Adoration of the Magi, c. 1857-1860

Private collection

4

Carl Spitzweg after Rembrandt

Self-Portrait of Rembrandt, c. 1860

Private collection

5

Carl Spitzweg after Rembrandt

The Apostle Paul in Prison, c. 1857

Private collection

Notes

1 [Gerson 1942/1983] German reproductive printmakers after Rembrandt, although they often only reproduced school pictures, include e.g. Joachim Martin Falbe, Johann Gottfried Haid, Georg Friedrich Schmidt, Valentin Daniel Preisler, Daniel Chodowiecki, Johann Friedrich Bause, Adam von Bartsch and Carl Ernst Christoph Hess.

2 [Gerson 1942/1983] Benesch 1924, p. 157

3 [Van Leeuwen 2018] On the impact of Rembrandt’s self-portraits on foreign artists of the 19th century: Rosales Rodríguez 2016, p. 320-346.

4 [Van Leeuwen 2018] On Marées: Lenz et al. 1987-1988.

5 [Gerson 1942/1983] ‘Holy Night’, auction A. Adelsberger, Munich 8.10.1930, no. 142. A free copy after Johannes Lingelbach was at the Spitzweg exhibition in Munich in 1908, no. 236 (later: auction Zickel, Munich 17 October 1934, no. 281). A painting attributed to Anselm Feuerbach in the auction Munich 20 June 1905, no. 470 (and Munich 21 December 1931, no. 19) was only a copy after Rembrandt (Hofstede de Groot 231). [Van Leeuwen 2018] On Spitzweg: Wichmann 2002. Spitzweg’s copy after Lingelbach: RKDimages 291714. The so-called Feuerbach: RKDimages 291715. According to Wichmann, Spitzweg copied a Rembrandt portrait (Wichmann 2002, p. 404, no. 969, ill), now in the Wallace Collection. It was formerly in Schloss Weissenstein, Pommersfelden, where Spitzweg probably copied it. the same goes for the copy afer Rembrandt's Apostle Paul in Prison (Wichmann 2002, p. 323, no. 688, ill.).