1.4 Dresden

Dresden was not only the city with the largest collection of Dutch art, but also the centre of contemporary artistic life, for which the Saxon kings August II (the Strong, 1670-1733) and August III (1696-1763), and scholars like Christian Ludwig von Hagedorn (1712-1780) and collectors like Heinrich Count von Brühl (1700-1763) were protectors. All cultural circles maintained close relations with French collectors and artists and especially the German Johann Georg Wille (1715-1808) in Paris engaged himself to be of service to his colleagues in Dresden.1 Wille was connected with the collector Gottfried Winckler (1731-1795) in Leipzig by a close friendship that transcended their commercial interests.

Most striking is the tradition of 17th-century still-life painting. The Leipzig painter Gottfried Valentin (1661-1711)2 made still-lifes in the manner of Willem van Aelst and William Gowe Ferguson [1-2].3 In Dresden it was Tobias Stranover (1684-1756) from Siebenbürgen [nowadays Transylvania, Rumania, ed.] who painted, like his teacher Jakob Bogdány (1660-1724), flower pieces, still-lifes with fruit and dead venison in imitation of Ernst Stuven [3], Abraham Mignon and Melchior d' Hondecoeter as supraportes and other wall decorations [4]. Later he followed his teacher to England.

1

Gottfried Valentin

Game piece with dead hare

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 641

2

Gottfried Valentin

Game piece with hound dead hare and pheasant

3

Tobias Stranover

Bunch of Flowers in Vase

Budapest, Hungrian National Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 3936

4

Tobias Stranover

A rooster, a hen, a pheasant and other birds in an extensive landscape

Denmark, private collection Alice (Baroness) Reyn

Ádám Mányoki (1673-1756) came from Hungary to Dresden, where he held the position of court painter from 1713.4 Not only in time but also stylistically he stands between Johann Kupezky (1665/6-1740) and Balthasar Denner (1685-1749). He was a pupil of Andreas Scheits (1655-1735) in Hamburg, but had trained himself in Holland.5 From the Dutch he adopted the fine painting [5-6].6 However, he dervied the elegance of the composition, that distinguishes his portraits, from his French models (such as Nicolas de Largillière, whom he copied) and from Anthony van Dyck [6-7].7

5

Ádám Mányoki

Portrait of Gustav Adolf Reichsgraf von Gotter (1692-1762), c. 1730-1731

Braunschweig, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, inv./cat.nr. 594

6

Ádám Mányoki

Portrait of Prince Francis II Rákóczi (1676–1735), c. 1710

Dresden, Szczodre, private collection Frederik August III (king of Saxony) (1865-1932)

7

Ádám Mányoki

Portrait of a young nobleman with a large perriwig, 1705-1706

Private collection

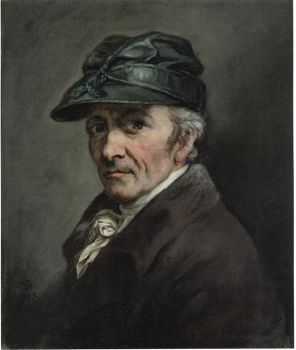

At the end of the ‘Old Art’ stands the Swiss portraitist Anton Graff (1736-1813) from Winterthur, who lived in Dresden since 1766, for which reason he deserves to be named here. When one sees his art in contrast with the elegant, sumptuous portrait style of the first half of the century, it becomes evident, how much he owed to the realism of the old masters, which he copied zealously as a young man. But Graff is much less into the old masters than the 13 years older (Sir) Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792). The type of self-portrait with the slanting light from above, that leaves the eyes in the shadow, possibly goes back to Rembrandt (like with Reynolds) [9-12].8 Josef Grassi (1757-1838) also painted such an artist’s portrait once [13].9

9

Anton Graff

Self portrait of Anton Graff (1736-1813), dated 1813

Leipzig, Museum der bildenden Künste Leipzig

10

Anton Graff

Self-portrait of Anton Graff (1736-1813), 1805-1806

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv./cat.nr. 2168

11

Anton Graff

Self portrait of Anton Graff (1736-1813), dated 1813

Berlin (city, Germany), Nationalgalerie (Berlijn)

12

after Rembrandt

Self-portrait with pen, inkpot and sketchbook, c. 1657

Dresden, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden - Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, inv./cat.nr. 1569

13

Josef Grassi

Portrait of the sculptor Anton Grassi (1755-1807), dated 1791

Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien

Notes

1 [Van Leeuwen 2018] On Wille and his circle: Décultot et al. 2009.

2 [Van Leeuwen 2018] In the time Gerson wrote the ‘Ausbreitung und Nachwirkung’, the lemma on Valentin had not appeared yet in Thieme /Becker 1907-1950. He mistakenly called this artist Georg Valentin and stated that he was active ‘between 1680-1750’, a highly unlikely long period anyway. His work should rather be called ‘Ausbreitung’ than ‘Nachwirkung’.

3 [Gerson 1942/1983] Braunschweig, no. 641. Auction Berlin, 5 February 1935, no. 190.

4 [Van Leeuwen 2018] On Mányoki: Buzási 2003.

5 [Van Leeuwen 2018] Prince Franz II Rákóczi sent him on a diplomatic mission to Holland, where he took the opportunity to study art (Saur 1992-, vol. 87 [2015], p. 92).

6 [Gerson 1942/1983] Brunswick, no. 594 (Portrait of A. von Gotter, Illustrated Biermann 1914, no. 58) [fig. 5, ed.].

7 [Van Leeuwen 2018] Mányoki studied portraits of Largillière in Salzdahlum when he was taught by Matthias Scheits (Thieme/Becker 1907-1950, vol. 24 (1930), p. 46 and other sources).

8 [Van Leeuwen 2018] Graff wore headgear to protect his eyes that were sensitive to light, probably because of cataract (Fehlmann et al. 2013, p. 46). Harald Marx points to the relationship with the portrait, considered as a Rembrandt at the time, but now considered to be a copy of an unknown and possibly lost painting by Rembrandt (Marx et al. 2003-2004, p. 118-119, no. 21, ill.).

9 [Gerson 1942/1983] Biermann 1914, vol. 2, fig. 680.